Zombie on the River

- Anne Moul

- Jun 3, 2018

- 5 min read

Updated: Apr 29, 2025

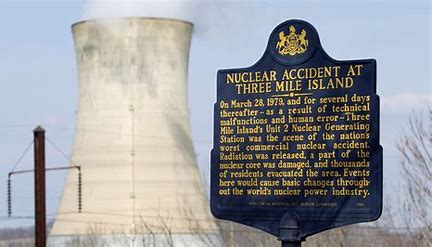

Chiques Hill, a high out-cropping of rock near my hometown in southcentral Pennsylvania, provides a breath-taking view of the Susquehanna river. To the north, like a vision of Oz, lie the giant cooling towers of Three Mile Island nuclear power plant. Thin white plumes of steam spiral out of the towers for Unit One, the only reactor still in use.

From up here, it all looks so placid, like a futuristic settlement on a far planet. I remember seeing the massive turbines roll through town on flatbed trucks, headed for the new power plant being constructed on a sandbar on the Susquehanna known as Three Mile Island. We just landed a man on the moon, and now this clean, modern energy produced without smoke or pollution, would be generated twenty miles north of us. Ten years later, on a day in late March, we heard about a minor incident occurring in unit two of the nuclear reactor. I was out shopping for wedding shoes with my mother. We listened to the reports on the car radio and then went to our favorite restaurant for lunch as planned. My mother was fighting breast cancer, so I was just happy to spend a normal day with her.

Outside there was no evidence of anything amiss.

No mushroom cloud or strange light in the sky. It was a typical end of March week in the mid-Atlantic, still more winter than spring. There was no assault on the senses that made you think something terrible had happened or was about to happen. We joked about holding our breath and glowing in the dark.

News reports told us that a pressure valve in unit two failed to close, and contaminated water drained into adjoining buildings, causing the core to dangerously overheat. Emergency cooling pumps were activated but human operators in the control room misinterpreted the readings and mistakenly shut down the pumps and the reactor. Residual heat from the fission process was still being released which caused the core to overheat to just 1000 degrees short of a meltdown.

Most of us had no concept of what any of this meant. Men in short sleeve dress shirts and narrow ties reassured us from our television screens that all was well. Governor Thornburgh, calm and professorial in his horn-rimmed glasses, initially suggested a precautionary evacuation of nearby towns but was quickly silenced by the corporate owners of the plant.

The core had come within an hour of a complete meltdown and over half the core was destroyed, but it had not broken its protective shell. No radiation was escaping. Sighs of relief. Crisis averted. No need to evacuate or scurry into those buildings with the ubiquitous yellow “Fallout Shelter” signs leftover from the Cold War days.

On March 30, we were told there was a bubble of highly flammable hydrogen gas within the reactor building created two days earlier when exposed core materials reacted with super-heated steam. The day of the incident, some of this gas exploded, releasing a small amount of radiation into the atmosphere. The sound at the time was attributed to a ventilation door closing. The experts weren’t sure if this bubble could create a further meltdown or possibly a giant explosion. Residents were ordered to stay indoors. The governor advised all pregnant women and young children who lived within a 5-mile radius to evacuate. The floodgates of panic burst open.

My uncle, a retired physician, who had been shepherding my mother through her cancer treatment, tells her it’s time to head out, especially for someone with a weakened immune system. Schools and businesses closed. We decided to leave until whatever was coming was over, if it was ever over.

Lines formed around gas stations, banks were emptied of cash, roads were jammed with cars packed with possessions. People who never dreamed they would be refugees suddenly found themselves leaving their homes, not knowing if they’d ever return. With the looming specter of nuclear annihilation now a reality, those duck and cover drills we did at school during the Cuban missile crisis seemed utterly absurd.

My parents went to the New Jersey shore to stay with my mother’s best friend from college. It was the last time they would see each other. For my mother, who found it ironic that she was being evacuated to avoid radiation exposure, this was a brief reprieve from her radiation and chemo treatments. By the first anniversary of TMI, she had been dead for a month.

I went to my fiancé’s apartment outside Philadelphia where we practiced being newlyweds while waiting for Armageddon. We were young and idiotic, so we drank cocktails and watched TV, cooked meals, and walked the dog, all the while pretending we were grown-ups, just in case we didn’t get to do it for real. We found it darkly romantic. Huddling together safe from the sinister bubble. Waiting for news.

We returned to our homes after President Jimmy Carter toured the plant in his haz-mat suit and reassured us that the danger was past. TMI became a touchstone, a reference point. “I started teaching the year TMI blew up.” “Our first child was born during TMI.” “We live just south of TMI.” To this day, I never think of those three letters as standing for “too much information.”

In the years following the accident, disturbing studies on cancer rates of those who lived within a close radius of the plant popped up on a regular basis, only to be quickly discredited by representatives of the company’s owners. Investigative reporters dug deep, but that data was banished into the far recesses of the state department of health. Hard copies probably now long destroyed.

TMI is once again back in the news because it is to be permanently shut down in 2019.

Nuclear energy generation is no longer profitable and at this point, the state is not going to bail out the company. This morning an article in the local paper described the potential dangers associated with long-term storage of nuclear waste. Beyond the environmental impact, there is concern that with reduced security at closed plants, the waste itself could be more vulnerable to attack by terrorists or anyone with a deadly agenda.

40 years after a nearly catastrophic nuclear event, the dancing atoms will at last be stilled. Insidious spores of radiation will no longer be spewed into the atmosphere. TMI will become an island wasteland, an abandoned behemoth rising out of the river, a permanent shrine to one of the greatest human screw-ups in modern history, its deadly innards sealed in lead and concrete but always with the potential to come back and destroy, given the right circumstances. TMI is our zombie on the river. It will never really die.

Comments